大众科学:那些用自己身体做实验的勇者(组图)

http://www.sina.com.cn 2010年12月20日 15:04 新浪尚品 [ 微博 ]

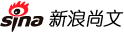

本月初,科学家分享了一位绝望的男子试图采用大胆行动来治愈自己疾病的故事:这名男子吞咽下了蠕虫卵。虽然如此,吃蠕虫卵的男子并不是首位以取得进步之名而采取极端行为的第一人。以下是一些为了科学有意使自己置身于不适、危险境地,甚至冒死亡风险的勇敢者们。还有许多其他例子,从将导管插入自己心脏的人到那些为试图找到治疗热带疾病方法而牺牲的医生。我们在这里向这些勇敢者致敬。

吞咽下蠕虫卵来治病

吞咽下蠕虫卵来治病深入活火山

阿尔帕德-基尔纳深入意大利正在喷发的特隆博利火山。他在火山上呆了三个小时,对液态熔岩进行研究。

深入活火山

深入活火山喝重水

挪威科学家克劳斯-汉森喝下了1夸脱的重水。

喝重水

喝重水喝下含霍乱病毒的水

马克斯-冯-佩腾廓福尔和他的一些学生喝下了一试管含霍乱病毒的水。他没有发病。

喝下含霍乱病毒的水

喝下含霍乱病毒的水给自己注入野兔病病毒

为了平息公众对多发性粘液瘤的担心,三位澳大利亚科家给自己注入了多发性粘液瘤病毒,他们没有发病。

给自己注入野兔病病毒

给自己注入野兔病病毒给自己注射取自他人疣处的血液

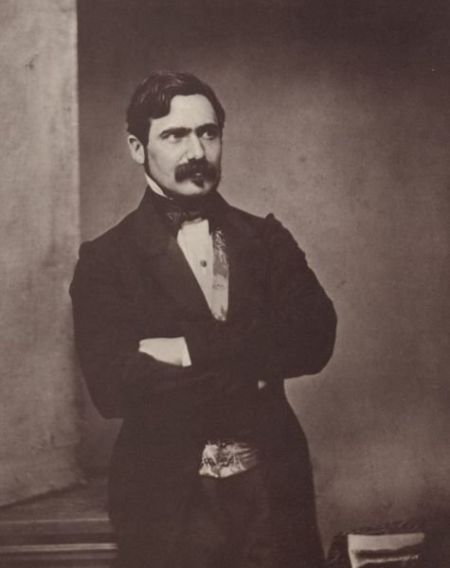

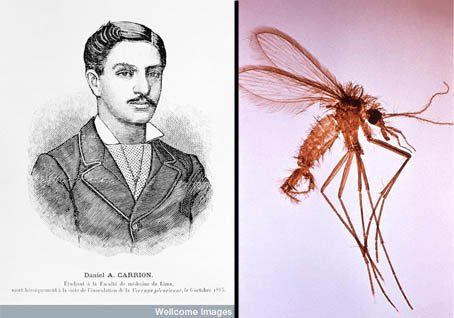

秘鲁医科学生丹尼尔-阿尔希德-卡里翁为了研究如何诊断秘鲁疣而向自己注射了取自他人疣处的血液。他随后死于与秘鲁疣相关的另一种疾病奥罗亚热。

给自己注射取自他人疣处的血液

给自己注射取自他人疣处的血液世界上最快的男子

约翰-保罗-斯塔普为了展现人类是如何应对极端快速加速和减速而志愿参加实验。他在1954年的一次测试中用五秒完成了从零至每小时632英里的速度,成为世界上最快的男人。

世界上最快的男子

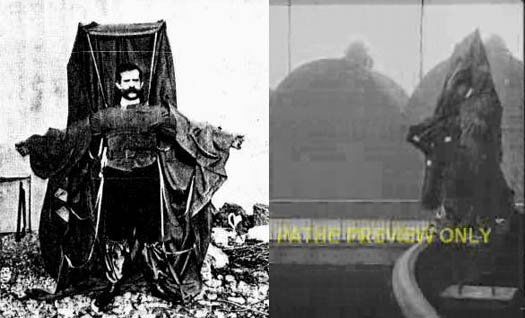

世界上最快的男子试验自制降落伞

奥地利裁缝弗兰兹-瑞切特设计了一种特制大衣降落伞。他从埃菲尔铁塔纵身越下,当场坠亡。

试验自制降落伞

试验自制降落伞Science's Favorite Self-Experimenters, Self-Endangerers, and Self-Agonizers

Earlier this month, scientists shared a tale of a desperate man whose daring effort to cure himself may have led to a new, albeit odd, medical treatment: swallowing worm eggs. But worm man is far from the first to take desperate measures in the name of progress. There’s a long line of heroes who have knowingly and willingly exposed themselves to discomfort, danger or even death for science’s sake。

And there are plenty of other examples. From the man who catheterized his own heart to the doctors who died seeking cures for tropical diseases, here we pay homage to a dozen of these brave souls。

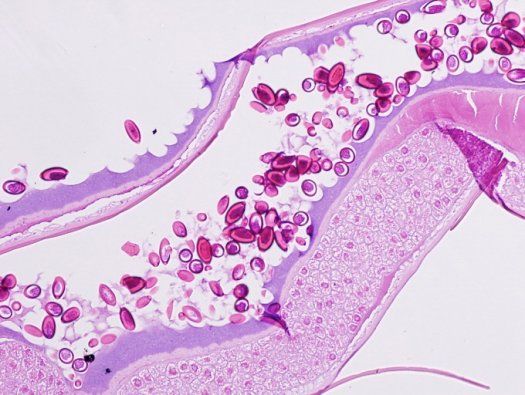

Descending Into A Volcano

A steel-armored, mustachioed man dangling by an asbestos thread 800 feet into the mouth of an active volcano may sound like a scene written by Dante. For Arpad Kirner, writing in the April 1933 issue of Popular Science, it was the definition of scientific adventure。

Kirner describes a hellish landscape in the bowels of Mt. Stromboli, a volcanic island off the coast of Sicily, in which the rocks are hot enough to boil water and the air reaches 150 degrees F. Kirner wore an asbestos suit and steel armor to protect himself from flying rocks, and spent three hours in the volcano, studying its “incandescent sea of liquid lava, agitated, boiling, shaken with convulsions。”

Other volcanologists have not been so lucky. On May 18, 1980, U.S. Geological Survey volcanologist David Johnston was camping on Coldwater Ridge, a few miles north of Mount St. Helens. Johnston had been studying the volcano since it began stirring in March, after a 123-year dormancy. At 8:32 a.m., he radioed the USGS base with his last words: “Vancouver, Vancouver, this is it!” The blast killed Johnston and 56 others. He was 30.

Don’t ever let anyone tell you rocks are boring。

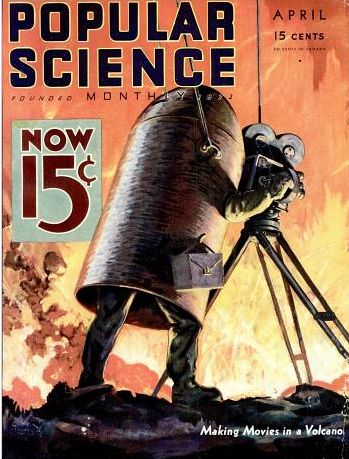

Drinking Heavy Water

Anyone who has ever licked a battery (which we are NOT recommending) has probably been intrigued by the tingly, buzzing sensation on your tongue. Perhaps it was similar to the sensation Norwegian scientist Klaus Hansen felt as he drank a quart of heavy water. He reported a “mild shock and burning lips,” according to the April 1935 issue of Popular Science。

Heavy water — which is denser than regular H2O and has a higher proportion of the hydrogen isotope deuterium — is poisonous to small fish and plants, but at the time, scientists didn’t know why. No one knew what would happen as Hansen took his first sip, so onlookers were armed with stomach pumps and defibrillators. He drank more each day to measure its effects, and two years later, when PopSci checked in to see how he was doing, he was “still enjoying the best of health。”

Large concentrations of heavy water are toxic because it prevents cell division. Today, its use is closely monitored because it can be used to produce plutonium from natural uranium, according to the Federation of American Scientists。

Drinking Cholera - And Living To Tell About It

Most scientists had come to accept germ theory by the late 19th century, partly because of the German bacteriologist Robert Koch, who discovered the bug that causes tuberculosis. Koch was convinced cholera, that other Victorian-era scourge, was also caused by germs, but one colleague was less certain。

Max von Pettenkofer thought cholera spread through the atmosphere, rather than from person to person, and to prove the germs were not enough to infect him, he and some of his students downed test tubes full of cholera. He didn’t get sick, and though some of his students developed minor infections, he claimed victory。

It was bittersweet, however. As author John M. Barry recounts in his book “The Great Influenza,” the water supplies of Hamburg and neighboring Altona were contaminated with cholera in 1892. Altona filtered its water, and Hamburg did not; Altona citizens did not get sick, while 8,606 Hamburgers died. Pettenkofer was reviled for his claims, and in a fit of depression, he killed himself, Barry writes。

Injecting Yourself With A Rabbit Disease

European rabbits were introduced to Australia in 1859, but without native predators and with an abundant food supply, they multiplied like, well, like rabbits. Nearly 100 years later, 600 million bunnies were competing with livestock for food and water, and authorities needed to do something。

They decided to introduce a rabbit disease called myxomatosis, and it worked wonders — 99 percent of Australia’s rabbits succumbed. It was the world's first successful biological control program of a mammalian pest, boasts the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, Australian's national science agency。

Shortly afterward, a human encephalitis epidemic spread through the state of New South Wales, and the public blamed myxomatosis. Hoping to quell their fears, three Australian scientists, Frank Fenner, McFarlane Burnet and Ian Clunies Ross, injected themselves with myxomatosis. They were fine, and the public’s fears were put to rest, according to CSIRO。

Injected With Blood From Someone Else's Wart

Some self-injectors are not so lucky. Daniel Alcides Carrión García, for whom Carrion’s disease is named, was a medical student in Peru who was studying Oroya fever and verruga peruana, particularly nasty diseases only found in Peru, Ecuador and Colombia. It is caused by a bacteria transmitted by sandflies like the one seen above。

Verruga peruana is usually a benign condition and is characterized by multiple disfiguring tumors, according to the Centers for Disease Control. Oroya fever involves fever and anemia and has a high fatality rate。

Carrión hoped to learn how to diagnose Verruga peruana before the tumors erupted, and decided the best way to learn was to inoculate himself. On Aug. 27, 1885, he used a lancet to inoculate his arm with blood taken from a wart above the right eyebrow of a 14-year-old boy。

The CDC gives the following account, taken from his diaries: “21 days after the inoculation, on September 17, Carrión felt discomfort and pain in his left ankle. Two days later, fever began. He also experienced chills, abdominal cramps, and pain in all the bones and joints in his body. He was unable to eat anything, and he commented in his diary that his thirst was devastating。”

He realized he was not suffering from verruga, but from a related illness, Oroya fever. “This is the evident proof that Oroya fever and the verruga have the same origin,” he wrote. He died Oct. 5, 1885.

The Fastest Man in the World

Astronauts have nothing on John Paul Stapp. The original Rocketman, as the Air Force fondly calls him, traveled faster than any other human and was also the fastest to stop. He volunteered to be a human decelerator in military crash tolerance tests, hoping to illuminate how humans handle extremely fast acceleration and deceleration. He’s seen here in one of his decelerator sled tests。

In a 1954 test, Stapp went from zero to 632 mph in five seconds, riding on a special rocket sled. He screeched to a halt in just 1.4 seconds, sustaining more than 40 g of thrust, according to the Air Force. That's the equivalent of hitting a brick wall in a car traveling at 120 mph。

Throughout his tests, he suffered rib fractures, retinal hemorrhages and two wrist fractures (the second of which he reset himself, the Air Force heritage program says). But he had no permanent disabilities; Stapp believed human acceleration tolerance was even greater than his studies showed。

Testing a Homemade Parachute

Not everyone can survive daredevil flight experiments, however。

A year after Wilbur and Orville Wright’s miracle at Kitty Hawk, an Austrian tailor designed a special overcoat-parachute thingy and expected it would help him fly, or at least glide. With a video camera rolling, Franz Reichelt leapt off the Eiffel Tower — and plunged quickly to his death。

The macabre video ends with men solemnly measuring the crater he left behind. Watch it here。

(大众科学)