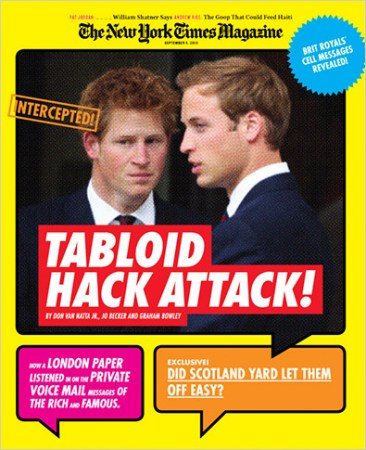

英国小报为获得名人秘密不择手段

http://www.sina.com.cn 2010年09月13日 14:27 新浪尚品

英国小报《世界新闻报》窃听皇室成员事件仍在不断曝出新内幕。新的证据显示,这并不是一起孤立的事件。从事窃听行动并不只是已入狱的《世界新闻报》前负责皇室报道的记者克莱夫-古德曼、私人调查员格伦-穆尔凯尔的个人行为。英国所有的小报记者都不惜采取窃听等不道德的手段来获得有关名人的报道素材。

伦敦大都会警察局收集到的证据显示,《世界新闻报》的记者可能窃听了数百位名人、政府官员、足球明星的电话信息。只是在《世界新闻报》记者窃听皇室成员丑闻被曝光四年后,这些遭窃听的人士才开始发现这一情况。至今年夏天,5人已提起了诉讼,指控默多克出版帝国下属的新闻集团报业窃听了他们的语音信箱。更多的诉讼仍在准备之中,其中包括一个要求对伦敦大都会警察局相关调查工作进行重新评估的官司。这些诉讼开始披露了窃听活动的规模。事实上,对警方档案、法庭文件和对调查人员和记者的采访表明,英国受人尊敬的警方机构未能追查相关线索,这些线索显示,作为英国最有权力的报纸之一,《世界新闻报》经常窃听英国公民的电话。

虽然警方2006年在穆尔凯尔住所发现了大量物证,但大都会警察局的注意力几乎一直集中在皇室成员遭窃听案,该案最终导致克莱夫-古德曼、格伦-穆尔凯尔入狱。当警方官员向检察官展示证据时,他们没有讨论有关从事窃听活动不只局限于这两人的关键线索。

曾两度对电话窃听事件进行调查的议会委员会主席约翰-威廷戴尔称:“大都会警察局对调查穆尔凯尔和古德曼以外人士的案件缺乏热情。对于他们来说,揭露编辑部广泛存在的不道德行为是一块他们不愿意去举起的重石。”数位调查人员在接受采访时称,大都会警察局不太愿意展开更大范围的调查的部分原因是它与《世界新闻报》关系密切。警方官员对他们的调查工作进行了辩护,称他们的责任并没有扩大至监管媒体。

伦敦大都会警察局只关注皇室成员遭窃听案的作法使《世界新闻报》和其母公司国际新闻可以继续声称,窃听行为只是古德曼的个人行为。但是在对《世界新闻报》十多位前记者和编辑的采访表明,情况恰恰相反。他们说,编辑部的气氛是疯狂的,有时甚至是堕落的,一些记者公开进行窃听行动或者其它不当作法以满足苛刻编辑的要求。一名记者将这种心态称为“为了报道不惜一切”。

并不是只有《世界新闻报》一家进行窃听行动以获得名人性丑闻报道材料。在为《世界新闻报》和其它小报工作时曾目击窃听行为的沙龙-马歇尔称:“这是一个行业内普遍存在的事情。与英国的任何一位小报记者交谈,他们都会告诉你每个电话公司的四字密码。每家报纸的所有工作人员都知道窃听活动的事情。”

Tabloid Hack Attack on Royals, and Beyond

IN NOVEMBER 2005, three senior aides to Britain’s royal family noticed odd things happening on their mobile phones. Messages they had never listened to were somehow appearing in their mailboxes as if heard and saved. Equally peculiar were stories that began appearing about Prince William in one of the country’s biggest tabloids, News of the World。

The stories were banal enough (Prince William pulled a tendon in his knee, one revealed). But the royal aides were puzzled as to how News of the World had gotten the information, which was known among only a small, discreet circle. They began to suspect that someone was eavesdropping on their private conversations。

By early January 2006, Scotland Yard had confirmed their suspicions. An unambiguous trail led to Clive Goodman, the News of the World reporter who covered the royal family, and to a private investigator, Glenn Mulcaire, who also worked for the paper. The two men had somehow obtained the PIN codes needed to access the voice mail of the royal aides。

Scotland Yard told the aides to continue operating as usual while it pursued the investigation, which included surveillance of the suspects’ phones. A few months later, the inquiry took a remarkable turn as the reporter and the private investigator chased a story about Prince William’s younger brother, Harry, visiting a strip club. Another tabloid, The Sun, had trumpeted its scoop on the episode with the immortal: “Harry Buried Face in Margo’s Mega-Boobs. Stripper Jiggled . . . Prince Giggled。”

As Scotland Yard tracked Goodman and Mulcaire, the two men hacked into Prince Harry’s mobile-phone messages. On April 9, 2006, Goodman produced a follow-up article in News of the World about the apparent distress of Prince Harry’s girlfriend over the matter. Headlined “Chelsy Tears Strip Off Harry!” the piece quoted, verbatim, a voice mail Prince Harry had received from his brother teasing him about his predicament。

The palace was in an uproar, especially when it suspected that the two men were also listening to the voice mail of Prince William, the second in line to the throne. The eavesdropping could not have gone higher inside the royal family, since Prince Charles and the queen were hardly regular mobile-phone users. But it seemingly went everywhere else in British society. Scotland Yard collected evidence indicating that reporters at News of the World might have hacked the phone messages of hundreds of celebrities, government officials, soccer stars — anyone whose personal secrets could be tabloid fodder. Only now, more than four years later, are most of them beginning to find out。

AS OF THIS SUMMER, five people have filed lawsuits accusing News Group Newspapers, a division of Rupert Murdoch’s publishing empire that includes News of the World, of breaking into their voice mail. Additional cases are being prepared, including one seeking a judicial review of Scotland Yard’s handling of the investigation. The litigation is beginning to expose just how far the hacking went, something that Scotland Yard did not do. In fact, an examination based on police records, court documents and interviews with investigators and reporters shows that Britain’s revered police agency failed to pursue leads suggesting that one of the country’s most powerful newspapers was routinely listening in on its citizens。

The police had seized files from Mulcaire’s home in 2006 that contained several thousand mobile phone numbers of potential hacking victims and 91 mobile phone PIN codes. Scotland Yard even had a recording of Mulcaire walking one journalist — who may have worked at yet another tabloid — step by step through the hacking of a soccer official’s voice mail, according to a copy of the tape. But Scotland Yard focused almost exclusively on the royals case, which culminated with the imprisonment of Mulcaire and Goodman. When police officials presented evidence to prosecutors, they didn’t discuss crucial clues that the two men may not have been alone in hacking the voice mail messages of story targets。

“There was simply no enthusiasm among Scotland Yard to go beyond the cases involving Mulcaire and Goodman,” said John Whittingdale, the chairman of a parliamentary committee that has twice investigated the phone hacking. “To start exposing widespread tawdry practices in that newsroom was a heavy stone that they didn’t want to try to lift。” Several investigators said in interviews that Scotland Yard was reluctant to conduct a wider inquiry in part because of its close relationship with News of the World. Police officials have defended their investigation, noting that their duties did not extend to monitoring the media. In a statement, the police said they followed the lines of inquiry “likely to produce the best evidence” and that the charges that were brought “appropriately represented the criminality uncovered。” The statement added, “This was a complex inquiry and led to one of the first prosecutions of its kind。” Officials also have noted that the department had more pressing priorities at the time, including several terrorism cases。

Scotland Yard’s narrow focus has allowed News of the World and its parent company, News International, to continue to assert that the hacking was limited to one reporter. During testimony before the parliamentary committee in September 2009, Les Hinton, the former executive chairman of News International who now heads Dow Jones, said, “There was never any evidence delivered to me suggesting that the conduct of Clive Goodman spread beyond him。”

But interviews with more than a dozen former reporters and editors at News of the World present a different picture of the newsroom. They described a frantic, sometimes degrading atmosphere in which some reporters openly pursued hacking or other improper tactics to satisfy demanding editors. Andy Coulson, the top editor at the time, had imposed a hypercompetitive ethos, even by tabloid standards. One former reporter called it a “do whatever it takes” mentality. The reporter was one of two people who said Coulson was present during discussions about phone hacking. Coulson ultimately resigned but denied any knowledge of hacking。

News of the World was hardly alone in accessing messages to obtain salacious gossip. “It was an industrywide thing,” said Sharon Marshall, who witnessed hacking while working at News of the World and other tabloids. “Talk to any tabloid journalist in the United Kingdom, and they can tell you each phone company’s four-digit codes. Every hack on every newspaper knew this was done。”

Bill Akass, the managing editor of News of the World, dismissed “unsubstantiated claims” that misconduct at the paper was widespread and said that rigorous safeguards had been adopted to prevent unethical reporting tactics. “We reject absolutely any suggestion or assertion that the activities of Clive Goodman and Glenn Mulcaire, at the time of their arrest, were part of a ‘culture’ of wrongdoing at the News of the World and were specifically sanctioned or accepted at senior level in the newspaper,” Akass wrote in an e-mail。

He accused The New York Times of writing about the case because of a rivalry with a competing media company。

In February, the parliamentary committee issued a scathing report that accused News of the World executives of “deliberate obfuscation。” The report created a stir yet did not lead to a judicial inquiry. And Scotland Yard had chosen to notify only a fraction of the hundreds of people whose messages may have been illegally accessed — effectively shielding News of the World from a barrage of civil lawsuits. The scandal appeared to be over, especially for Coulson, who had been hired by the Conservative Party to help shape its message in the run-up to the general election. In May, when David Cameron became prime minister, he rewarded Coulson with the top communications post at 10 Downing Street。

But the hacking case wouldn’t go away. Two victims notified by Scotland Yard sued the paper and negotiated agreements, one for a million pounds. Emboldened, lawyers began rounding up clients and forcing the Metropolitan Police (known as Scotland Yard) to reveal whether their names were in Mulcaire’s files. Cases are being brought by a member of Parliament, a woman who was sexually assaulted when she was 19 and a prominent soccer commentator who happens to work for one of Murdoch’s companies. “Getting a letter from Scotland Yard that your phone has been hacked is rather like getting a Willy Wonka golden ticket,” declared Mark Lewis, a lawyer who won the first settlement. “Time to queue up at Murdoch Towers to get paid。”

FOR DECADES, London tabloids have merrily delivered stories about politicians having affairs, celebrities taking drugs and royals shaming themselves. Gossip could end careers, giving the tabloids enormous power. There seemed to be an inverse relationship between Britain’s strict privacy laws and the public’s desire to peer into every corner of other people’s lives. To feed this appetite, papers hired private investigators and others who helped obtain confidential information, whether by legal or illegal means. The illicit methods became known as “the dark arts。” One subspecialty involved “blagging” — getting information by conning phone companies, government agencies and hospitals, among others. “What was shocking to me was that they used these tactics for celebrity tittle-tattle,” said Brendan Montague, a freelance journalist. “It wasn’t finding out wrongdoing. It was finding out a bit of gossip。”

Steve Whittamore, a private investigator who worked for numerous tabloids, himself became the subject of headlines in 2005, after the authorities seized records from his home that revealed requests by hundreds of journalists for private information. “There was never an instance of me doing anything other than what I was asked,” said Whittamore, who now runs a Web site that tracks local crime. He eventually pleaded guilty, though no journalists were ever charged. Among Whittamore’s clients was News of the World, where he worked for 19 reporters and editors。

Rupert Murdoch purchased the once-sleepy Sunday tabloid in 1969. Although the paper was not immune to the industry’s decline — its circulation is now 2.9 million, down from 4 million a decade ago — it remains a powerful presence. Sex scandals aside, the paper has exposed wrongdoing resulting in dozens of criminal convictions。

Murdoch unabashedly uses his London papers — which also include The Sun, The Times of London and The Sunday Times — to advance a generally conservative, pro-business line. Beginning in the late 1970s, his papers supported Margaret Thatcher and the Conservative Party, attacking her Labour Party rivals in editorials and news articles. Years later, Labour’s Tony Blair assiduously courted and won Murdoch’s backing for his more-centrist politics. “You had huge influence as editor,” said Phil Hall, who ran News of the World from 1995 to 2000.

One standout at News International was Andy Coulson, who made his name as a young reporter in the early 1990s writing for The Sun’s showbiz column. A native of blue-collar Essex in southern England, Coulson had a sharp instinct for what readers wanted. He famously once asked Prime Minister Tony Blair and his wife, Cherie, whether they were members of the mile-high club. In 2000, Coulson moved to News of the World as second in command under the editor, Rebekah Brooks. When she left three years later, Coulson, only 34 at the time, was the obvious choice to succeed her。

(文章节选自《纽约时报杂志》)

(解雨)